6 Ways to Create a Culture of Helpful Feedback

According to research from Gallup, most people don’t feel the feedback they receive at work is effective. What’s more, managers agree, with an overwhelming majority citing they’re not sure how to give feedback that’s specific enough to be effective. Offering guidance and feedback that’s kind, clear, specific and sincere is the foundation of Radical Candor.

In order to make Challenging Directly while also showing you Care Personally easier to do, we break it down in a way that’s easy to remember. Radical Candor is HIP: Humble, Helpful, Immediate, In person, Public praise/Private criticism, not Personalized. If you’re not sure how to give helpful feedback, this post is for you.

1. Get clear about how you intend to help

Take a moment to think through the reason why you plan to deliver the feedback. If you are clear in your own mind about how your feedback will be helpful, it will come across to the other person naturally. But if you don’t understand why your feedback is helpful, how will the person receiving it?

2. State your intention to be helpful

Perhaps the simplest advice I have to give here is for you to tell the person that you are trying to be helpful. Try a little preamble for hard criticism. For example, try saying, in words that feel like you, “I’m going to tell you something because if I were in your shoes I’d want to know so I could fix it.” Simply exposing your intent to be helpful offers clarity to the other person about your intentions. Most people will want to hear whatever it is you’re going to say.

3. Show, don’t tell

This is the best advice I’ve ever gotten for writing good fiction—but it also applies to feedback. The more clearly you show what is good or bad, the more helpful your feedback will be. Often you’ll be tempted not to describe the details because they are so painful. You want to spare the person the pain and yourself the awkwardness of uttering the words out loud. But retreating to abstractions is a form of Ruinous Empathy.

Being precise can feel awkward. For example, I once had to say, “When we were in that meeting and you passed a note to Catherine that said ‘Check out Elliot picking his nose–I think he just nicked his brain,’ Elliot wound up seeing it. It pissed him off unnecessarily, made it harder for you to work together, and was the single biggest contributing factor to our being late on this project.” It was tempting just to say, “Your note was childish and obnoxious.” But that wouldn’t have been as clear or as helpful.

The same principle goes for praise. Don’t say, “She is really smart.” Say, “She can do the NYT crossword puzzle faster than Bill Clinton,” or “She just solved a problem that no mathematician in history has ever been able to solve,” or “She just gave the clearest explanation I’ve ever heard of why users don’t like that feature.” By showing rather than telling what was good or what was bad, you are helping a person to do more of what’s good and less of what’s bad, and to see the difference.

Important note: if you are getting feedback, and somebody fails to give you a specific example, don’t demand that they come up with one. That will make them feel cross-questioned and reluctant to give you feedback next time. Instead, say, “So what I hear you saying is that when I do X, Y happens. Is that right?” Then, try to think of a specific example yourself. Don’t worry if you can’t think of one on the spot. Think of it later. When you do, tell the person and ask, “Is that an example of what you mean?”

4. Finding help is better than offering it yourself

You’re not always the best person to give help, and it isn’t possible for you to offer help yourself every time you give feedback. If you put too much of a burden on yourself to fix every problem you see personally, you will stop bringing problems up. But, you often can do something quickly that will help. When Sheryl offered to get me a speaking coach, she did have to get budget for it, but she didn’t have to sit there watching me practice presentations for hours. It took some of her time, but not too much.

When Scott Sheffer, who worked for me at Google, was struggling with a strategic problem, it was clear he needed a great thought partner. Scott was one of the most strategic people I knew, and understood the business better than I did. I wasn’t the right person to help him. He needed to talk to somebody who’d seen the problem a hundred times before, somebody with decades more experience than either he or I had.

The person he most longed to talk to was Bill Campbell, the legendary Silicon Valley coach. I knew the thing I could do that would be most helpful was not to try to spend hours helping him think through the problem, but to spend twenty minutes getting him some time with Bill. That’s what I did.

5. Feedback is a gift, not a whip or a carrot

It took me a long time to learn that sometimes the only help I had to offer was the feedback itself. Adopting the mindset that feedback is a gift will ensure your feedback is helpful even when you can’t offer actual help. Don’t let the fact that you can’t offer actual help make you reluctant to offer feedback. Think about times that feedback has been most helpful to you, and offer it in that spirit. If you can’t think your own story, recall how helpful it was for me when Sheryl told me I sounded stupid when I said “um” every third word.

6. Share the context

A great way to offer praise that is helpful is to share the context so that everyone understands why the work was important, and what the impact was. Putting the work into a broader context is generally something a boss can do better than anyone else. Often, people who do the work don’t even realize the impact it has.

For example, Sarah Teng, a woman on the AdSense team came up with the idea of buying programmable keypads for the whole team. This simple idea increased the whole team’s efficiency by 20%. This meant that everyone on the team had to spend 20% less time on “grunt work” and had more time to come up with other ideas to improve efficiency — a virtuous cycle.

I wanted to explain this virtuous cycle to her and to the whole team. I wanted her to know just how great I thought what she did was. Often people are not actually aware of the positive impact they’ve had with their work, and letting them know helps move them in the right direction.

I said it in public for two reasons. One, and people often pay more attention to things said in public than in private, so I thought it would mean more to Sarah. Also, I wanted everyone else to speak up when they had ideas like that. So when she presented her project to the team, I thanked her, and I also showed a graph of how this idea, and others like it, had improved our efficiency over time.

I let the team know that she would have an opportunity to share her idea with leaders from AdWords, a much larger team, for an even larger impact. I also shared an article from the Harvard Business Review (HBR) showing how competitive advantage tends to come not from one great idea but the combination of hundreds of smaller ones. All of this context showed how important her idea was and inspired people who had other ideas like this to be vocal about them.

A version of this article by Kim Scott, the author of the New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestseller Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss without Losing your Humanity and the co-founder of Radical Candor LLC, appeared on the Radical Candor blog.

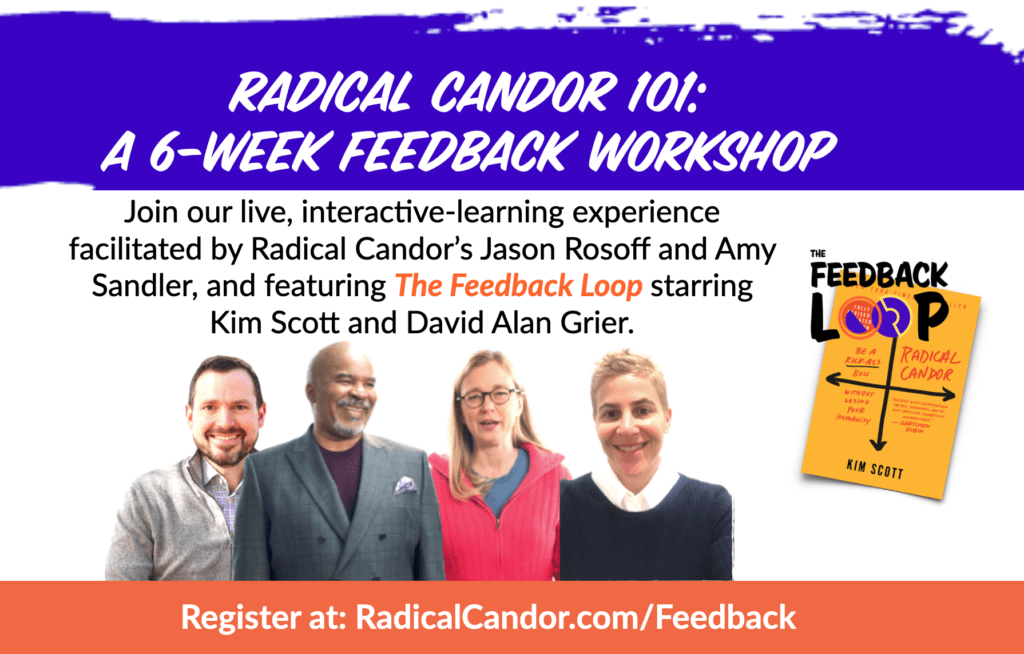

Improvising Radical Candor is a co-production of Radical Candor, LLC and Second City Works. By exercising Radical Candor through improvisation, teams learn the art of giving and receiving feedback while developing core improv fundamentals that emphasize skills like active listening, staying present and being others-focused. Want to learn more? Get The Feedback Loop, our workplace comedy series and supporting learning materials, starting at $59 for our self-paced e-course.