Kim Scott In Conversation With Kelly Leonard: Radical Candor Podcast Season 2, Episode 1

The Radical Candor podcast version 2.0 is here! The first episode is a special discussion that originally aired as a live conversation between Kim Scott and Kelly Leonard, partners in the new venture Improvising Radical Candor.

Read the Podcast Transcript

Jason Rosoff: Again, thank you so much for joining us for what we hope to be the first of many of these types of conversations. I’m Jason, I’m the CEO of Radical Candor. Why don’t I turn it over to Kelly Leonard, who is the author of Yes, And, and our partner at Second City Works. Kelly, take it away.

Kelly Leonard: Thanks, Jason. Hi everybody. Welcome. Thank you for joining us. I am the executive director of learning and applied improvisation at The Second City. I’m here with Kim Scott. The first thing we’re going to do is talk about this idea of checking in and I’m going to hold that for a second cause we’re going to do it.

Then we’re going to talk about the Radical Candor framework. And then I’m going to give you a little bit of insight into what we mean when we say that you should have an improv mindset, especially in a crisis. And then we’re going to talk about how to lead, collaborate and stay connected inside a crisis. And there are three areas we’re going to cover: building trust through caring and challenging, transparency and authenticity and we’re going to give you some practical tips that you can use at the end.

So Kim, one of the things that you and I have talked about is this importance, especially right now, what was important before, but especially right now of what it means to check in. So how are you?

Kim Scott: Things are looking up today. My husband was quarantined, isolated in our house. He went down to this little room off the garage and I was kind of slipping food onto the top of the stairs above the garage and he was creeping up to get it. And obviously I was pretty sure he was OK. But it’s always a worry and I just missed him. And I missed his help as well. So I’m really happy to report that he has no fever and is back up with us.

Kelly: Good. Good, good, good. So I’m in the attic of my home in the Northwest side of Chicago, which is where I’ve been working. So if you hear a bark or two, that is my 100 pound Bernese mountain dog named Benchley. Cause you know, that happens. Uh, and I’m doing okay. I mean literally the last two weeks have been The Second City taking a 60 year old live entertainment and training company and turning it into an online entertainment and training company.

But it’s actually kind of working. We have 80% retention and our students per training center and we’re gonna start doing shows on Zoom, hopefully as soon as next week. So yeah, it’s, it is like, I was scared like everyone’s scared, but also sort of marveling at the ways people are coming together. And we can, you and I touched on this this morning, right when we were looking at Twitter and an academic out there who said that actually in a crisis, more people do behave well than, than don’t.

Kim: Thank you for sharing that with me this morning, that was very comforting. Cause I think one of, one of my anxieties is that the social fabric is going to come unraveled, and the evidence is that it will actually be strengthened by the crisis. It won’t be weakened.

Kelly: Yeah. I think that’s an important way to enter it. And it’s not to minimize people’s suffering. It is not to, you know, not pay attention to the stark reality, which is not good. But as human beings, you know, we know that we do not operate at our best when we’re in our fear brain. That is not the way that we operate best. So much better to work from a growth mindset that’s very akin to an improv mindset. And then it calls for this level of clarity and communication, which is total Radical Candor. So I think that’s probably the best place for us to explain the framework for those people who might not know what Radical Candor is.

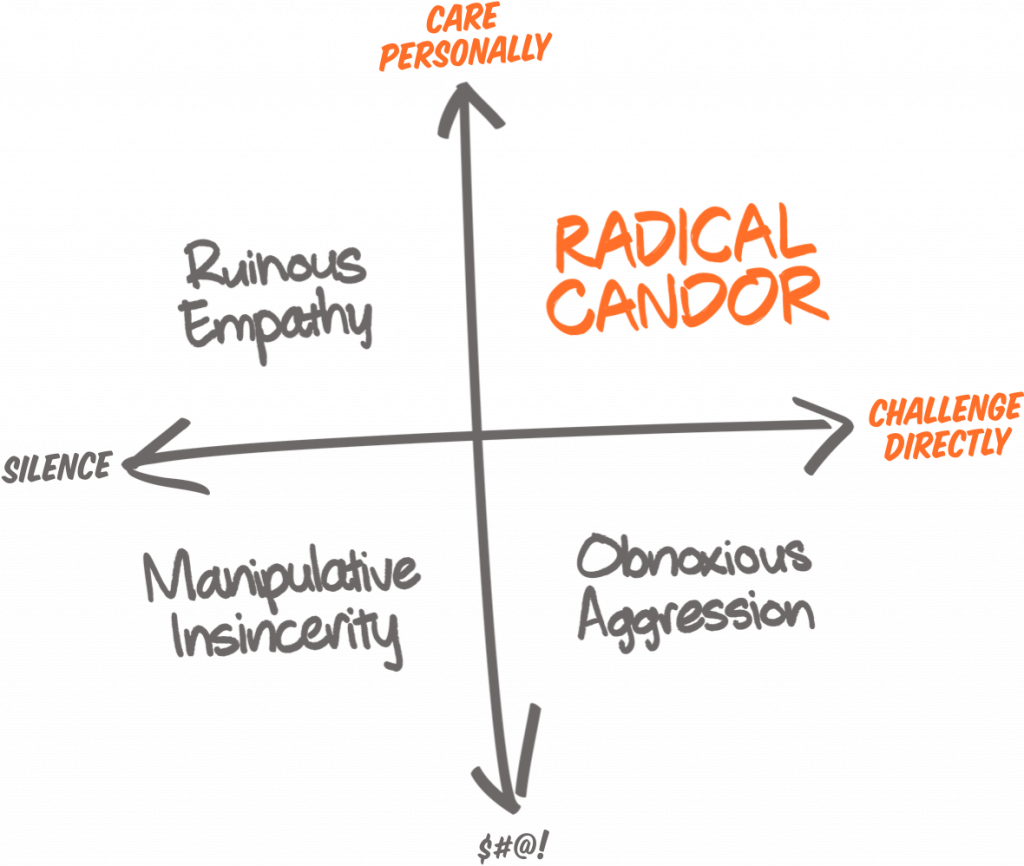

Kim: Great. So the idea of Radical Candor is actually really simple. It’s about Caring Personally and Challenging Directly at the same time. And I think the good news is that I’ve seen some of the best examples of this that I’ve ever seen, both from leaders and also from, from the guy who was checking me out of the grocery store the other day, like where people really take a moment to do what you just did for me, Kelly, and to check in with one another, but also to to say when they need some help. So for example, the Radical Candor I got in the grocery store was the guy who was checking me out was that I had to bag the groceries myself, which I should have figured out myself, but I needed him to tell me.

So that was a little Radical Candor, and I appreciated it. And then as I was bagging, we had this very kind of intimate and satisfying conversation about how our respective families were doing. So that’s a small example of Radical Candor in the moment. However, it’s also important to understand what Radical Candor is not.

We said that very often a crisis brings out the very best in people, but occasionally it brings out the worst. And I think it’s more important than ever to learn how to hold up a mirror to people when the crisis is bringing out their worst. So one of the things that happens very often when we’re stressed out is we act in a way that I call Obnoxious Aggression.

That’s where you do challenge someone else, but you fail to tell them that you really care. So I was trying to get my kids to help me vacuum before I came up here and I’m afraid I fell into the Obnoxious Aggression quadrant even though the other day when we talked, I promised I wouldn’t do that (and that time it was about the dishes).

It’s so easy when we’re stressed out to remember to challenge people, but to forget to show them that we care. And I think that more now than ever, it’s important to start with that, that sort of reminder to ourselves and to others of our shared humanity.

Now sometimes what happens in a crisis is kind of the opposite of Obnoxious Aggression. It’s what I call Ruinous Empathy. And that’s where we’re so concerned about the people around us and we realize that they are stretched to their limits so we don’t tell them something that they really need to know.

It’s really important in a time of crisis to remember that compassion is so important and truth is equally as important. If you sort of abstract Radical Candor out to its most abstract level. It’s about love and truth at the same time. So Ruinous Empathy is what happens when you do remember to show love, but you forget about the importance of, of sharing your truth.

And last but not least, there is Manipulative Insincerity and this is the very worst way to respond to a crisis, although it’s also very human. So we need to have compassion for ourselves. And not use this framework to judge ourselves or to judge other people. But Manipulative Insincerity is what happens when we don’t say what needs to be said and we forget to show that we care about the other person. We just kind of pull into our shell, turtle like, and of course we all need to do that from time to time, we need a little bit of self care.

But don’t forget to re-emerge from your shell and see the people around you and to show them that you love them. Shower the people you love with love, like never before, but, but love is not all we need. We also need truth. Tell them the truth about what’s going on. Does that make sense, Kelly?

Kelly: Yeah, and I think it’s also important to know that this isn’t static conditions, right? All of us are floating between these at any given time, which is why understanding that when you do fall into Obnoxious Aggression, it’s going to happen. So then you can pivot and move into the more Care Personally. So you can, you can move from a bachelor’s aggression to Radical Candor. If you grab onto your care and the person across from you knows that you care, right?

Kim: Yes, exactly. And I think it’s also important to remember that you want to move in the right direction, not in the wrong direction when you find yourself in a quadrant you don’t want to be in. So very often when we realize we’ve acted like a jerk, the temptation is to move the wrong direction on Challenge Directly rather than moving the right direction on Care Personally. So if you realize you’ve been a jerk, don’t say, “Oh, I didn’t really mean it. It’s no big deal” if it is a big deal, but do take a moment to show that you care.

Kelly: So one of the reasons I think it’s important to understand that these aren’t static conditions is because that’s a thing improvisation does. Practice in a world that is constantly being written in the moment, so you know, when groups of people are making nothing and making something out of nothing, that’s a very, very hard thing to do. So we have all these training exercises. And they teach people to see all obstacles as gifts. To make mistakes work for you. We have the notion that all of us are better than one of us. And we have a concept called follow the follower, which in essence is the servant leadership model.So it actually emanates out of a game. And the game is where a group of students are in a room and they’re told to walk around the room, sort of slowly making eye contact.

One person is secretly told they’re the leader and their job is to find someone to trade off that leadership with. So you have to, without speaking, trade off that leadership and then someone will pick it up and then they do the same. And it was funny, we were demonstrating this at the Spiritus Institute here in Chicago many years back and my friend was like, you guys are doing Peter Drucker. And I was like, I don’t know who Peter Drucker is. So now I do, a cutting edge management theorist and consultant who believed way long ago that hierarchies are not the best way to get things done. And that individuals need to lead at every level that they’re at. And when we are too hierarchical, that’s when problems happen.

And I host a podcast called Getting to Yes, And and, and I remember having Eric McNulty from Harvard, [who wrote a] terrific book called You’re It, and was researching the response to the Boston Marathon bombing. And when he went to go look for who the leader was, there wasn’t one. What everyone did was knew how to lead, how to trade off, and they trusted each other. And they were very well prepared because there’s so many of these historical events that happen in Boston that their crisis management team was already put in place. And so I think we can kind of see the effects of this right now. What or who has the teams and who has the mindset that they are going to be able to move swiftly, communicate with each other clearly, and then who doesn’t.

Kim: Yes. We’re seeing a lot of that. I’ve certainly noticed some of the best examples of leadership and some of the worst examples. So one of the best examples I saw recently was a leader who gave everybody on their team four-day weekend when we went into working from home and said, take Friday and take Monday and figure out how you’re going to rearrange your life and so that you can take care of whoever is at home with you and then also how you can still show up for work when possible.

And this person also sort of identified what work still needed to be done, but also identified work and asked the team to identify work that they could just stop doing for this period in recognition of the fact that this situation puts a lot of burden on everybody. You can’t offer the same solution. People who are at home alone need different things than people who are at home with six kids who need to be educated.

So that’s one of the best examples. One of the worst examples I’ve seen is as a leader who installed spyware basically on everybody’s computer so that they could see how long everyone was working every day. And so that was, that was to put it mildly, not helpful for morale. And you know, that’s kind of a funny story, but in all seriousness, can we get political just for a second here a little bit, a little bit? We’ve seen some of the very worst examples of, of leadership. We’ve seen leaders who are spouting arbitrary BS, who are pretending that they know when they don’t know, which is very dangerous.

And we’ve seen some great leadership recently. I was watching [New York Governor] Cuomo talk recently. And I think he does a few things really well. He, first of all, remembers to show he cares personally. He said the other day, we’re not sacrificing anybody. Everybody is important. So he remembers to show humanity.

And at the same time, he tells the truth even when the truth is a little bit scary. But he gives the numbers and people can deal with big challenges. But this total uncertainty is what is so hard to deal with. So when he has numbers and facts to give, he gives them and he also takes action. So, he said, you know, there are four things we need to do. Social distancing, testing — and they took action on testing. He gave the numbers, he said until February 28 only 472 people had been tested in the United States by the CDCs tests, which weren’t working that well.

And he actually lifted a bunch of bureaucracy and allowed a New York Department of Health to develop its own test. And that made a big difference to New Yorkers. He talked about masks and the importance of masks. (By the way, there’s this great website called masksnow.org. This is something you can put your kids to work making masks and it can actually make a big difference.) And he talked about ventilators, so social distancing, testing, masks and ventilators.

And in many ways when Cuomo said that New York needed 30,000 ventilators, that was scary. But, it was also very specific. He used research, not guessing, and it’s achievable. He also said, here’s what the government can do and here’s what the government can’t do. The government can lift regulations so we can experiment. So for example, he’s allowing an entrepreneur who is trying to retrofit a diving mask as a ventilator. He said, yes, we’ll buy some of those. We’re going to experiment. And I think it has galvanized people so that, it’s almost like, people know what they can do to help and they’re doing it.

Kelly: Yeah, that’s true. You know, for the last 10 years, people have been asking when we’re going to teach our politicians how to improvise. And it feels like it’s always felt like a daunting, impossible task. And how fantastic would it be if there was sort of a constant bipartisan action on behalf of everyone no matter, you know, who’s stripe you are. But this also speaks beautifully to the first thing we’re going to talk about, which is building trust through caring and challenging. What are the first things that you think of when you think about building trust?

Kim: It’s really interesting. I think at the very core of leadership is building trust. And Ryan Smith, who is the CEO of a company called Qualtrics, which some of you might know was one of the people who I coached, zeroed in on this very early in his tenure as CEO. And one of our first coaching sessions, he asked me, he said, “I’ve just hired this new team. How can I build trust quickly with that team so that we can get great things done?”

And so do you mind if I read something from my book because I love improvising, but I also love editing. Here’s the answer I sort of gave Ryan about how to build trust quickly. First of all a quote from John Stuart Mill, “The source of everything respectable and man, either as an intellectual or a moral …”

I think what he really meant is people not man to edit John Stuart Mill. But anyway, “The source of everything respectable and man either as an intellectual being or as a moral being, is that his errors are corrigible. He is capable of rectifying his mistakes by discussion and experience, not by experience alone. There must be discussions to show how experiences can be interpreted.”

And this I think is so important in a crisis. Love is important, but truth is also really important. So let’s think about what that means for your leadership and how to build trust as a leader. Challenging others and encouraging them to challenge you helps build trusting relationships because it shows one, you care enough to point out both the things that aren’t going well and those that are, and two, that you are willing to admit when you’re wrong and then you’re committed to fixing mistakes that you or others have made. But because challenging often involves disagreeing or saying no, this approach embraces conflict rather than avoiding it. So it’s so tempting in a crisis to avoid conflict, but resolving conflict — and resolving it quickly — is one of the things that we can do to build trust.

Kelly: So in improvisation, trust is at the root of our ensembles.We don’t use the word team. We use the term ensemble, which implies that there are values, ethics and behaviors that everyone has to adhere to in order for the group to be successful. Everyone’s probably heard the phrase, your group is only as good as its weakest member. We don’t believe that. What we believe is your group is only as good as its ability to compensate for its weakest member. Because at any point, one of us is going to be the weakest member. I mean, if you start throwing math problems at me, I am the weakest member. If you want me to talk about improv, I’m not the weakest member. But you know, again, we don’t live in static times and especially, we know that in a crisis.

And I think it was Ernest Hemingway who said, “The best way to find out if you can trust someone is to trust them.” Starting with intent, thinking good intent — we very often move into our fear brain. That is how we were built. You know, we had been running on the Savannah much longer than we’ve been running for the bus, right? So we’re built to recognize these dangers. So when you know that, you need to do the switch. And I love this phrase: Replace blame with curiosity. But you know, that’s often a very hard and tricky thing to navigate. I think of the study that Amy Edmondson did, and she coined the term psychological safety, which is all about trust.

So she was a grad student at Harvard, and they were studying high performance nursing teams at this hospital outside of Boston. And they had assumed that the highest performing teams would make the fewest mistakes, but what they discovered was actually the highest performing team made the most mistakes. So she had to dig in and figure out what was going on. And it took her a little while. But it wasn’t that the lowest performing teams were making the fewest mistakes, it was that they weren’t reporting their mistakes at all.

So this is at the root. One of the worst things that can happen in a crisis, or frankly anytime, is organizational silence. And Radical Candor itself is the enemy of organizational silence. I think that our marriage of improv practice and Radical Candor theory is what makes this like a superpower.

So let’s also talk about the next thing that we had here, which is transparency and authenticity. Where do you come down on that? What’s important about that?

Kim: Transparency — showing what you do know is so, so, so important. Especially right now. The leaders who are sharing the facts and figures with their teams are the leaders who are building trust with their teams, the leaders who are saying, “I’m going to show you our runway. I’m going to show you how, you know, how much money we have so that we can all develop a plan to move through this crisis together,” are the teams that are really coming together to come up with the most innovative solution.

So I think that transparency is really vital in terms of information. I also think that privacy is important in terms of building relationships. So taking the time to have those private conversations, those, those one-on-one meetings, which we’ll talk about later, it’s also really important. At the same time, authenticity is really important. Equally as important as transparency.

Kelly: Vulnerability is a strength. I don’t understand when people don’t [think] it is. It takes courage to be vulnerable. And we know from our work with the behavioral science community, human beings desire to be seen and heard. That is what they’re looking for. Nature abhors a vacuum. And in times like this, people assume silence equals bad news. It instills fear.

When leaders are transparent and authentic, their teams assume that good intent, which means their teams won’t be working out of fear. And you can’t innovate or be creative when you’re working out of your fear brain.

I oversaw Second City auditions for decades and we’d seen thousands of people, right? Just coming off the street. And as they would walk up on the stage, I would mark down the people who were not gonna make it. It was easy because they were shaking.

Literally, you’re sweating or like they were not. And it’s not like the Tina Fey’s and the Stephen Colbert and the Steve Carrels weren’t nervous before going in, but they found a practice by which to turn their stress into positive stress to be a peak performer. My friend Alison Wood Brooks at Harvard, I was talking to her one time about the fact that I was out doing public speaking when my book came out and that I got nervous like everyone does and she goes, “I got a trick for you. Before you go speaking, don’t say out loud you’re nervous. Say out loud, I’m excited.”

And literally I do that now all the time. It switches the brain a little bit and gets you in that performance mode. There’s a tradition at Second City too. Before we go on stage for any show, or before we enter a workshop, this is [back] when we could be in a room together, we pat each other on the back and say, “got your back.”

Kim: And you did this for me — sorry to interrupt. I can’t help myself. But you did it for me in a virtual way right before the beginning of this because I was a little nervous. I haven’t, this is as Brené Brown said, an FFT. I think that means fucking first time. And I said, I was nervous and you told me, say I’m excited, channeling the energy of fear into the energy to be creative. It made a big difference. And then telling me that you had my back also really mattered. So thank you. It worked!

Kelly: It does work. And, and you know, look, I have some firsthand knowledge about being highly vulnerable in a crisis because I’ve lived there for the last two years. In 2018 my daughter Nora was diagnosed with cancer. We spent a year fighting it and she passed away in August and Kim knows — she’s been along this journey with us.

One of the things that we did was we took all this knowledge that we have from science and all our improv stuff, and we messaged and we blogged every day and we asked for help when we needed it. And what happened was we built a community that didn’t exist before and it was many different communities, friends, you, people I had met once suddenly jumped in and they were able to send these messages, whether they’re videos or gifts or whatever.

So this last year, as terrible as it was, it had meaning. And the absence of meaning ruins everything. It kills everything. So at least we had that and can’t, I mean, Kim, you saw this, I think, you know from your vantage point, right?

Kim: It was really incredible. And I think the important thing to remember is that when you told people what was going on and when you asked for help, your asking for help was actually an act of generosity because everyone around you loved you and wanted to help and didn’t know what to do. And so allowing us to know enough about what was going on to know how we could help was a real act of generosity and leadership.

Kelly: Thank you. I mean the idea right now is when you are truthful with your people, when you ask for their help, they will do it. And I’m seeing this at Second City. I mean these things that we’re building, like no one is saying no. I mean everyone is jumping in and supporting each other and it’s a beautiful thing. But we have some practical tips we want to share for folks. So do you want to give yours and then I’ll give mine?

Kim: Sure. Absolutely. So first of all, if you’re doing any kind of meeting, whether it’s a one-on-one meeting or a staff meeting, begin with a check-in. Take just a moment, and it doesn’t have to take tons and tons of time, but take a moment to see how people are doing. Because we all are seeing into one another’s lives in a way that we never have before. It’s very unusual.

I was talking to someone who said they were on a call with their boss and their boss’s kid ran through and all of a sudden their boss seems like much more of a vulnerable human being. So we’re literally seeing into one another’s living rooms, and if you take a moment to check in with people, that actually turns what could be a stress and a distraction into a positive.

So take the check in time. If you have a team, I would recommend doing shorter one-on-one meetings. Instead of a once a week one-on-one meeting, have three 10-minute meetings every week because a lot happens in a week right now and you don’t get the kind of texture of what’s going on for people right now that you did before when you just would walk by them and kind of see how they were.

So, try having shorter meetings. Also, sometimes shorter meetings are easier to fit into home chaos for people. I think a tip is be conscious of what you can do asynchronously because that tends to be more efficient and convenient and what you need to do synchronously. So, tasks can get done asynchronously. Bonding needs to be synchronous.

There are times when I think if you have a big team in a different time zone, occasionally work on that time zone. It’s a little bit of a pain in the neck here. You’re up at odd hours, but you create more synchronous time for them.

And finally, make listening tangible. Be very conscious also of how much time everyone is speaking. There’s evidence that shows that teams on which everyone speaks roughly the same amount of time, actually perform better than those where one person dominates. So if you want, get yourself an app and measure how much, what percentage of a meeting you talk, and if you talk more than your fair share, learn how to shut up a little bit. That’s my struggle. And if you talk less than your fair share, remember that you’re not doing anybody any favors by withholding your thoughts. Sharing your thoughts is an act of generosity.

Kelly: I got, I got one of those apps and the results were not pretty. I had to learn to shut up. That’s something we share. Here are my five. Listen to the end of everyone’s sentence before you respond. So an improvisation, we have an actual exercise where you have to start your sentence with the last word the other person said, and then they have to do the same. Try that exercise and you are gonna realize that you don’t listen to the end of sentences. You start planning your response. But yeah, listen to the end. You might learn some information.

Cede the need to be right. Avoid group mind and instead utilize group intelligence. We’ve all seen the studies on the importance of diversity. In groups you want different points of view, [the ability to] speak truth to power, those sorts of things.

Make sure there is a clear meeting agenda and that everyone is actually aware of it. I’m saying this virtually cause it’s really, really important, but you will also recognize that we needed it before. So if we learn anything out of this nightmare, it will be like shorter meetings with clear agendas that everyone knows in advance.

Designate one person to lead and run the meeting. These virtual meetings are a performance. You are on a stage and you need a director. You do not want director-les ensembles running around, that is dangerous. And keeping it aligned with the performance aspect, you need good lighting, facing toward a window is good.

No need to be in a suit and tie, but don’t wear a bathrobe. Pick a good stage, just a spot in your home that is as quiet as possible and you won’t be distracted or become a distraction to others, but then also — use the cute dog or cat coming in. Let your kids say hi. We actually love that. That has happened on so many of my meetings and it has made for, as Kim said before, a real authentic experience.

I know that Jason is assembling some questions right now.

Jason: So a very tactical question first, mostly for you, Kelly. Do you have any thoughts about how to practice this idea of follow the follower virtually? Is there an idea or a brainstorm that you might have to help teams do that?

Kelly: I thought about this the other day because many of you I assume have these maybe somewhat small team meetings — I think we should pick a different person to run the meeting every time. So in doing that everyone gets practice in being the leader and moving it around. And so if they’re not good at it, that can be figured out and we can deal with that. And if they’re very good at it, we can sort of applaud it.

Jason: Next question. I’m curious how you both think about practicing Radical Candor with someone who seems at least to be unwilling to accept the sort of impact of their actions. And so I think, you know, Kim, you refer to this as sort of speaking truth to power. [What are your] thoughts about that, especially in this moment, because I think maybe those actions are causing extra harm.

Kim: Yeah. Those actions can be causing enormous harm. So if you had the boss who installed malware on your computer, how do you go to this boss and tell this boss, that’s a terrible, terrible, unproductive idea. So I think a couple of things are important. One is no matter who you’re speaking to, whether it’s your boss, your peer, or your employee, your spouse, your partner, your child, it’s important to start by soliciting feedback.

Don’t dish it out until you prove you can take it. And there are a couple of reasons for that. One is you want to make sure that you understand where that person is coming from and that you give yourself the opportunity to express some compassion for where that person is coming from. That boss who installed the malware probably wasn’t the raging asshole that he seems to be from his action.

He probably was really afraid about what was going to happen when everybody wasn’t in the same place at the same time. So making sure that you understand where that person is coming from is important and what that person feels about your actions, like what you might be doing or not doing that’s contributing to the situation. So start by soliciting. It doesn’t have to be some long drawn out root canal conversation. It can just be a couple of minutes.

And then you want to make sure that you focus on the good stuff. I think it is so important. Sometimes we have feedback debt and when there’s feedback debt in a relationship, when somebody’s been doing something that has been bothering you for a long, long time, there comes a point where that’s all you can see about that person and you’ve forgotten about all the things that you actually appreciate about working with that person.

So if you try to take a step back, take a deep breath and remember the good stuff, focus on the good stuff for a moment, then it becomes easier to say, look, there’s something that’s bothering me is now a good time to tell you. Follow that order of operations, feedback, focus on the good stuff. Again, all of these are two-minute conversations. Then it becomes easier to offer some candid criticism in a way that is both helpful and humble. Does that help?

Kelly: Yeah, I think that’s right on. I was thinking about this also at an organizational level. So if you have some power in your organization to make things happen, you need to set up some structures where truth can be spoken to power. Basecamp does a thing where, I think at the end of every year, they do an award show for the biggest failure.

Basically as a way to signal we want you to take risks and try things. It’s good and we’re going to celebrate this failure. At The Second City, we have a far more direct truth-to-power thing and it’s called The Second City Holiday Party. And what happens at the holiday party is the night staff and day staff (non-actors) put on a show that basically lampoons all the executives.

And I remember one year the waitstaff put on the song that they sang directly to our owner, where they said to him, “You can dress up a pair of jeans, but why do, why does the staff not have health insurance?”

I was just sinking in my chair. Like, they’re going to get fired. I’m gonna get fired. But that didn’t happen. What happened was the next day [the owner] brought the executive team in and said, “How do we get them insurance?”

And we got them insurance. That would not have happened if there weren’t a format. So that’s important to think about. If you have some leadership opportunities, create formats for truth to be spoken to power.

Kim: Yeah. Creating not just a format, but like you gave people the stage quite literally. So you want to think about, you want to think about ways to give people the stage to talk to you in a way that works for your organization.

I used to use this thing called whoopsie daisy where I’d bring in a stuffed daisy and ask people to confess the biggest mistake they made that week. And I would of course start with my screw up. And it was like there was a big celebration of who screwed up the worst that week and simple things like that can really make failure safe and create a more innovative organization.

Kelly: So what was your biggest whoopsie daisy here this week?

Kim: Oh wow. That is a good question. I think my biggest whoopsie daisy this week was I’ve been trying to teach children to diagram sentences because that’s what I learned to do in fifth grade. And I lost my temper with them a little bit in a way that was not productive. And my son actually wrote, and then I asked them to write a paragraph in their journal and my son wrote: “Mom, this is a pandemic, everyone is stressed. Just relax a little bit.” So I got a little bit of Radical Candor from him.

Kelly: Yeah. All right. My biggest whoopsie daisy is, I did a podcast taping, and then I’m on my last question when I look up and realize I never hit record. I haven’t told these guys yet. I just, I couldn’t. I finished the podcast. I thanked them and then I told Kim about it and she’s like, you’re going to tell them, so I will, they’ll find out this week.

Jason: How does vulnerability, compassion and honesty work in the transition to virtually mediated conversations? What should we be, what should be on our minds as we do that? I think, during your conversation, you talked about, we can kind of see into each other’s houses now and so there’s like this earned vulnerability or maybe this sort of unearned vulnerability that people are being sort of forced to be a part of. How do we think about that? And I think the related question is what can we do to practice? So like, we recognize that this is different. What should we be trying to improve? And then do you have any suggestions about what we could practice to help us get better?

Kim: Sure. I think one of my favorite examples yesterday came from a woman who I think she’s either a senator or a congress woman, but she was on a call with a bunch of other senators and congress people. And she thought she was on mute and she called out to her daughter, “Go to the potty and wash your hands. Mommy will be down there in a minute.” She tweeted this. And she said there were two former presidential candidates on the call and then Amy Klobuchar said, “that was my favorite part of the meeting.”

And so I think all of a sudden, our humanity, whether we intend for it to be or don’t intend for it to be, is on display. And I think very often, especially for a woman, we tried to pretend like these domestic things are not interfering in our work and you can’t pretend anymore right now.

And I [loved] the courage to not only laugh at it in the moment, but to tweet it out and to share it publicly because so many other people are having these experiences. And that’s a funny example. I mean, I think Jason actually, on a call with the Radical Candor team, you showed a lot of vulnerability as a leader describing an experience you and your wife had, and we all started crying, all everyone on that call, teared up. And it was really, an important moment for us to have because we all needed a cry. I told my husband afterward about the call and he teared up as well. And so I think that being willing to show vulnerability and to laugh and cry together is more important than ever.

Kelly: So I think about this when I look at the World Economic Forum always gives out their future work skills list. And coding is not on the list. The list includes divergent thinking, problem solving, innovation, creativity. And all the things that are deeply human because we are entering the technology age where the robots are going to be doing a lot of our work. And so the work that’s going to be left is all the stuff that is most human. And the problem is we don’t practice being human. We don’t practice listening. We don’t practice speaking. But what’s so odd about this is like the arts gets this — we rehearse, sports gets this — these millionaire baseball players play catch because it is that important in terms of practicing skills.

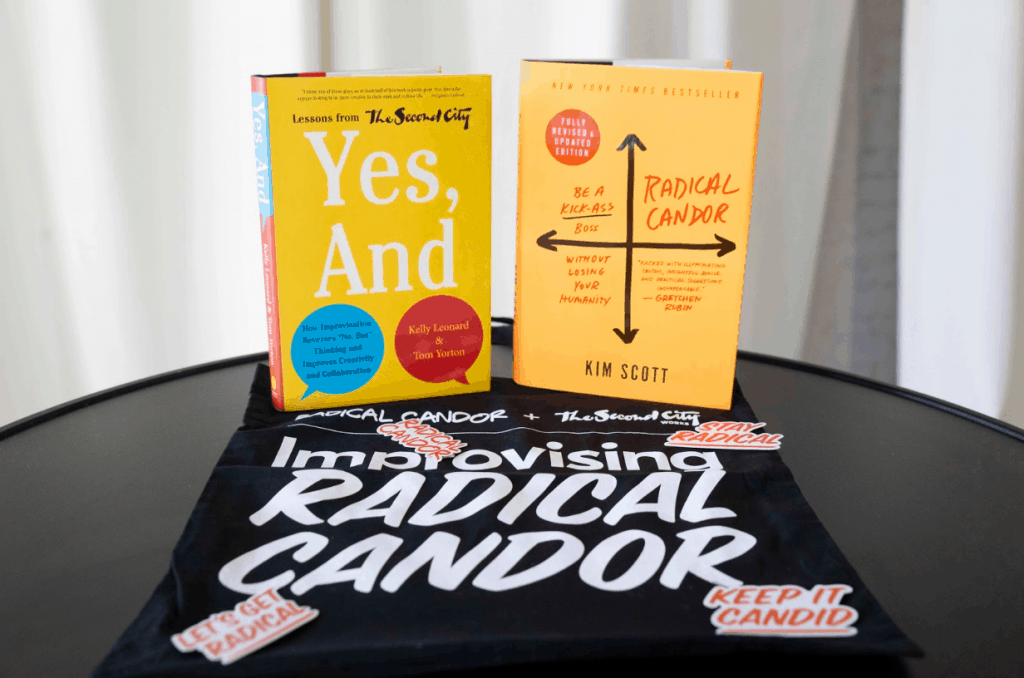

And this is different from role-playing, and I’m not putting down role playing, it has its place, but it’s like if you’re scrimmaging all the time, that doesn’t work. You have skills that you need to bring in to your performance and they change. So if you go to the back of the book I co-wrote with Tom Yorton, Yes, And, we actually just list out like a bunch of these improv exercises, the Yes, And game, and we used to do this with our kids all time, we’d do a game called one word story where we tell a story one word at a time, and this was to get them to stop fighting in the back of the car, but it also taught them how to share a conversation. So I think that this idea is, we have to be more human, which means that we have to pay attention to what it means to be human, which involves practice.

Kim: I think that is so important. Practicing, practicing our humanity. We do need drills. This is one of the things I learned after Radical Candor was published. It’s so easy for me to say, be radically candid, but so hard to do. It’s hard for me to do it. That’s why I wrote the book. It’s not like it’s easy for me either.

And one of the things I’ve loved about working with you and The Second City, Kelly, is that you do have these humanity drills, like these very specific ways to practice very specific skills. It’s not the whole conversation, but here’s how you practice listening. Here’s how you practice responding when you don’t like what you heard, when you listen. And I think it has been great fun to begin to break down the skills and give people some drills in specific human skills.

Kelly: We talked about the importance of meaning earlier. Meaning is made in moments and made in these interactions. And culture can be broken in moments, and we’re all going to do it. So recognize your mistake rate. This is the analogy I always give, which is, if you go into a job interview and you failed 70% of the time, you probably think you’re going to be fired.

But if you’re a major league baseball player and [that’s] your batting average, then you’re hitting 300. I mean we make more mistakes than we get it right. So we are in experimentation, especially right now. So you have another shot at it. You can use your other shot at it. And this is why the Radical Candor framework is so great. It gives you the cue to Care Personally so you can Challenge Directly. Just keep thinking about that, show your love and truth and we will get through this together.

Candor Checklist

1. Listen to the end of everyone’s sentence before you respond. We have an improv exercise where you have to respond to someone by starting your response with the last word they said — try it — you’ll realize you don’t listen to the end of sentences.

2. Cede the need to be right — avoid group mind and, instead, utilize group intelligence.

3. Make sure there is a clear meeting agenda that everyone is aware of.

4. Designate one person to lead and run the meeting. These virtual meetings are a bit of a performance and they need a director.

5. Keeping in line with the performance aspect: good lighting — facing toward a window is good; no need for a suit and tie, but don’t wear a bathrobe; pick a good stage — a spot in your home that is as quiet as possible and you won’t be distracted or become a distraction to others.

6. Start each meeting with a check-in. When people know what’s going on for one another the sudden visibility into each other’s living rooms is less distracting; we can better interpret why someone might be sharp or short; and it’s natural to care more when you know more.

7. For 1:1 meetings virtually, have shorter meetings more frequently. A lot happens in a week. And it’s hard to set aside a full hour if one of you has kids with frequent needs. Shorter calls are easier to fit into chaotic days. And you might even try opportunistic calling rather than trying to fit to a schedule.

8. Be conscious of why you are using synchronous meetings. Any work that can get done asynchronously, do it that way so everyone can manage what’s going on in the background. But synchronous calls are really important for bonding. Asynchronous efficiency, synchronous bonding.

9. If you have a team in a very different time zone, try working on their time zone once in a while to give more space for synchronous communication.

10. Be conscious of how much time you are talking versus other people in meetings when you work from home. If you’re taking up more than your fair share of time try to be more quiet. If you are not speaking up, remember that it is an act of generosity to share what you are thinking. If you are leading the meeting, consider occasionally just going person by person in alphabetical order. Teams that speak roughly an equal amount of time perform better than teams where one person takes up all the airtime.

11. Sometimes replicating in-person activities remotely can work. If you both get a cup of tea, a video call can feel more human. Take an extra moment to talk about something beautiful you saw, or something funny you heard.

12. Focus on being a partner, not an absentee manager or a micromanager. This is always important, but it’s even more important to remember when your whole team is remote. Remember that everyone is different, which is why you need to ask each member of your team what works for them. While some people may want to hop on the phone several times a day to talk, others might find this disruptive and stressful. Don’t assume that what works for one person will work for every person.

13. Most importantly, remember to be kind…All this social distancing can leave people feeling lonely. A few extra minutes to connect with people who work from home is time well spent.

Kim Scott is the author of the New York Times and Wall Street Journal bestseller Radical Candor: Be a Kickass Boss without Losing your Humanity and the co-founder of Radical Candor, LLC.

Kelly Leonard is the executive director of insights and applied improvisation at Second City Works. He is also author of the book, Yes, And: Lessons from The Second City.

Improvising Radical Candor, a partnership between Radical Candor, LLC and Second City Works, produces live and virtual content, including the new workplace comedy series The Feedback Loop, to help people practice Radical Candor through improv.